The importance of nutrition in cancer care

Precision nutrition aims to tailor dietary advice to fit the specific needs of an individual1. This is particularly important for patients undergoing cancer treatment, in order to minimise weight loss and malnutrition. Malnutrition and weight loss, affects up to 56%2 and 70%3 of cancer patients respectively. Both factors actually lower cancer treatment tolerance, leading to reduced chemotherapeutic dose3. High-protein, high-energy diets are often required to circumvent this weight loss. This may seem at odds with current healthy eating guidelines, however, cancer is a unique scenario, wherein energy and nutrient requirements can be quite high, as cancer really affects metabolism, and appetite is often poor4.

Despite increasing awareness that specialist dietitians should be included as core members for many cancer types, inadequate resourcing means that most tumour MDTs have limited or ad-hoc dietetic service provision at best. It is estimated that between 1/3 to 2/3 of malnourished cancer patients receive no nutritional advice5. A study conducted in Irelands 9 specialist oncology centres by Lorton et al., which included 200 patients, the majority of which had gastric or hepatobiliary cancer, found that referrals to a dietician in both inpatient and outpatients were “reactive rather than proactive”, in response to weight loss. 45% of dietician referrals should have been made sooner according to the oncology dietitian while only 1/3 of patients received nutritional screening2. A survey of malnutrition in Ireland conducted by Sullivan E.S et al., in 1073 cancer survivors shows similar results with only 39% of those surveyed having been assessed by a dietician. This is despite 45% of this group having diet related problems and 89% of responders saying diet was ‘very/extremely’ important in cancer care, highlighting just how many of these patients need and want dietary guidance6 .

However, lack of referral is not the only hurdle cancer patients must overcome to receive sound nutritional advice. Currently, there is only 1 dietician per 4500 cancer patients in Ireland making access limited6. According to Professor John Reynolds of St James’ Hospital and Trinity College Dublin, a leading expert in Gastric Cancer, it would cost €1.6 million to hire the necessary oncology dieticians and provide services for the 10,000 cancer patients in need of nutritional screening each year. This cost, however, could be off-set by savings made in the cost of treatment, as malnourished cancer patients have longer hospital stays, suffer increased chemotherapy toxicity and dose reduction, frequent hospital readmission and reduced quality of life (QOL)7,6. Indeed, a landmark study in Australia determined that the cost benefit of screening for malnourished patients outweighed the cost of putting these screening systems in place8.

The main goal of cancer nutrition is improvement or indeed maintenance of nutritional status, with a particular focus on maintaining lean mass9. Lean mass refers to body weight excluding fat mass (concentrated in adipose tissue), wherein skeletal muscle mass is a large component. This will reduce treatment associated side effects, aid post-surgery recovery and improve patient’s QOL. Cancer patients are one of the most malnourished group in the hospital setting8. Many patients have nutrition ‘barriers’ that prevent them from eating normally such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting and difficulties in swallowing2. Cancers of the digestive tract cause the most severe weight loss, while some like breast cancer can cause weight gain or no changes in weight at all2. Work conducted by Dr Oonagh Griffin in St Vincent’s University Hospital Dublin demonstrated that unintentional weight loss and resultant malnutrition can be easily missed in patients who were obese prior to diagnosis10. When creating a nutrition plan for these patients, it is important to take their individual symptoms, cancer type and personal tastes into account. For those with difficulty swallowing, softer foods and things like soup which are easy to swallow are key for getting in calories and nutrients. Resources recommend eating smaller more frequent meals rather than 3 large meals which can lead to people feeling full quickly. A patient centred cookbook created by Dr Aoife Ryan and Eadaoin Ni Bhuachalla called ‘Good nutrition for cancer recovery’ is an amazing resource full of high protein, calorie rich recipe ideas (Figure 1). It also includes advice for patients at the beginning of the cookbook for each barrier they may face, for example ‘Avoid greasy, spicy and sugary foods with strong odours’ for those with nausea and vomiting11.

Figure 1: Good nutrition for cancer recovery

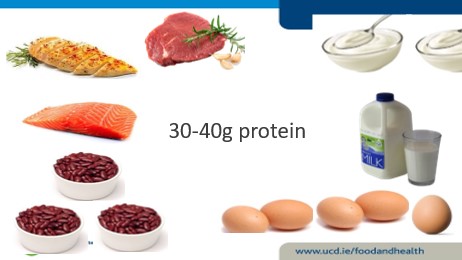

When your appetite is poor, achieving adequate energy and protein intake is challenging. Protein is essential for maintaining lean mass, tissue repair and also helps patients withstand the effects of chemotherapy and prevent further weight loss. Protein requirements for healthy individuals is 0.8g/Kg each day, this increases to 1.2-1.5g/Kg per day for cancer patients12. Therefore, a woman weighing 60kg would need around 90g of protein a day. Or a 90kg man would require 135g per day. To put that in perspective, Figure 2 presents food portions that deliver 30-40g of protein. A medium sized chicken breast (100 grams), for example, provides 31 grams of protein. However, many patients do not meet the protein requirements for healthy individuals, not to mind cancer recommendations, due to treatment and/or symptom related side effects. Protein is particularly important for those with cancer cachexia. Cancer cachexia refers to the rapid unintentional weight loss, particularly associated with significant loss of lean body mass, seen in many cancer patients. Patients with cachexia have an altered metabolism which shifts away from muscle building towards the breakdown of muscle13. A study conducted in UCC in foregut cancer patients found the prevalence of cachexia to be as high as 62%14. It is a complex response to malignancy and/or cancer treatments of which there are few treatment options. However, maximising protein and energy intake is paramount for these patients to minimise its affects.

Figure 2: What 30-40g of protein looks like in food. It is equivalent to ~ ¾ L skimmed milk, 5 boiled eggs, ¾ chicken breast or ~ 3-4 oz of cooked mince.

As well as ensuring adequate levels of fat and protein, vitamins and minerals are an important part of any diet but especially cancer patients. As cancer can adversely affect appetite and eating habits, many cancer patients may not get their recommended amount of essential vitamins and minerals15. It is estimated that 72% of cancer patients are vitamin D deficient16, compared to 20% of the general population17. Vitamin D is obtained through vegetables (vitamin D2), oily fish, fortified foods and the exposure of skin to sunlight (Vitamin D3). It is responsible for a healthy skeletal system and helps regulate calcium in the body15. The VITamin D and OmegA-3 TriaL (VITAL) was a large randomized clinical trial in 25,871 men and women that investigated whether dietary vitamin D3 or fish oil supplementation reduced the risk of developing cancer. While vitamin D supplementation did not significantly reduce cancer incidence, post-hoc analysis of the 5-year primary prevention study demonstrated a possible reduction in fatal cancer with vitamin D supplementation, depending on subject’s body weight18. Advanced cancers (metastatic or fatal) were significantly reduced following vitamin D supplementation if the subjects were not overweight or obese. However, it is important to note that evaluating Vitamin D status in the acute phase of inflammation or cancer is a challenge. C-reactive protein, a common marker of inflammation, is associated with lower serum 25(OH)D (vitamin D) levels and therefore may not be an accurate reflection of vitamin D status. In addition, 90% of vitamin D is bound to vitamin D binding proteins so measuring free serum levels may not give the most accurate result19,20. More work is needed in this area to improve our understanding of micronutrient status, including sensitive methods of measuring Vitamin D, in the presence of cancer.

Despite the importance of adequate vitamin and mineral intake, specialists do not advise exceeding the recommended daily dose. If a patient is struggling with food intake a multi-vitamin can be taken but it is imperative to consult with the oncologist before taking any new medication. As vitamins and other herbal supplements are not well regulated, it can be difficult to know what you are truly getting. Herbal remedies might seem harmless but some such as St John’s wort has been shown to decrease the efficacy of certain medications including chemotherapy21. As dietary advice for patients can be lacking, it is natural for those with cancer to seek information online. While there can be many great resources for patients, such as the cookbook I mentioned above as well as the Memorial Sloan Kettering integrative cancer centre, there is also a lot of false information out there. Extreme diets that cut out entire food groups and claim to cure cancer can do more harm than good. It is best to consult your doctor before making any drastic changes to your diet.

Receiving a cancer diagnosis can be a devastating time in a person’s life. Patients are often given lots of information at once and it can be difficult to take it all in. Diet may not even enter a patient’s mind until they start to experience symptoms that affect their eating and by then it may have already affected their weight. Conversely, adopting dietary changes may be at the forefront of some people’s minds as it may be the only component of treatment they feel can choose or control. Dietician referral should be integrated into first line cancer care, not just after surgery or when major weight loss has occurred. This could help save the lives of many patients, giving them the accurate information they need to make well informed decisions about their health. To make this possible, nutritional screening, well defined referral criteria and education and resourcing of relevant dietetic staff is necessary to bring about the necessary changes and improve the lives of cancer patients.

About the Author

Rianna started her PhD in January 2020 with Professor Helen Roche in UCD. Her project is focused on finding a biomarker for individuals with cancer cachexia and sarcopenia in the hopes of determining who will benefit from the drug Anamorelin by Helsinn.

Authors: Rianna McElroy (1), Oonagh Griffin(1)(2) & Helen M Roche (1)(3).

Affiliations:

1. School of Public Health, Physiotherapy and Sports science. UCD Conway Institute of Biomolecular and Biomedical Research, University College Dublin, Belfield, 4 Dublin, Ireland.

2. National surgical centre for pancreatic Cancer, St Vincent’s University Hospital, Dublin 24, Ireland.

3. Nutrigenomics Research Group, UCD Institute of Food and Health, UCD Conway Institute of Biomolecular and Biomedical Research, University College Dublin, Belfield, 4 Dublin, Ireland.

References:

- Juan de Toro-Martín BJA, Jean-Pierre Després,Marie-Claude Vohl. Precision Nutrition: A Review of Personalized Nutritional Approaches for the Prevention and Management of Metabolic syndrome. Nutrients; 2017. p. 913.

- Cliona LM, O G, K H, F R, G S, N G, et al. Late referral of cancer patients with malnutrition to dietitians: a prospective study of clinical practice. Supportive care in cancer : official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020;28(5).

- Louise Daly, Ross Dolan, Derek Power, Éadaoin Ní Bhuachalla, Wei Sim, Marie Fallon, Samantha Cushen, Claribel Simmons, Donald C. McMillan, Barry J. Laird, Aoife Ryan. The relationship between the BMI‐adjusted weight loss grading system and quality of life in patients with incurable cancer. 2020;11(1):160-8.

- Maria Rohm AZ, Juliano Machado,Stephan Herzig. Energy metabolism in cachexia. EMBO reports: EMBO reports; 2019.

- Xavier Hébuterne EL, Mauricette Michallet,Claude Beauvillain de Montreuil,Stéphane Michel Schneider,François Goldwasser. Prevalence of malnutrition and current use of nutrition support in patients with cancer. JPEN Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition. 2014;38(2).

- ES S, N R, E K, A K, JV R, J F, et al. A national survey of oncology survivors examining nutrition attitudes, problems and behaviours, and access to dietetic care throughout the cancer journey. Clinical nutrition ESPEN. 2021;41.

- Kim DH. Nutritional issues in patients with cancer. Intestinal research2019. p. 455-62.

- AG B, JM L, BL S. Using a public hospital funding model to strengthen a case for improved nutritional care in a cancer setting. Australian health review : a publication of the Australian Hospital Association. 2013;37(3).

- Norleena P. Gullett VM, Gautam Hebbar, Thomas R. Zieglerc. Nutritional Interventions for Cancer-induced Cachexia. Curr Probl Cancer.2012. p. 58-90.

- Neil B, Oonagh G. Nutritional considerations for the management of the older person with hepato-pancreatico-biliary malignancy. European journal of surgical oncology : the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology. 2021;47(3 Pt A).

- Good Nutrition for Cancer Recovery – a nutritional resource for the treatment of cancer‐induced weight loss - Ní Bhuachalla - 2016 - Nutrition Bulletin - Wiley Online Library. Nutrition bulletin. 2021;41(2):151-4.

- P R. Nutrition in Cancer Patients. Journal of clinical medicine. 2019;8(8).

- T A, KP T, A R, H M, K T. Cancer cachexia, mechanism and treatment. World journal of gastrointestinal oncology. 2015;7(4).

- LE D, ÉB NB, DG P, SJ C, K J, AM R. Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2018;9(2).

- Kurt A. Kennel MTD. Vitamin D in the cancer patient. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care.2013. p. 272-7.

- Ali A, Berna KE. Vitamin D deficiency in cancer patients and predictors for screening (D-ONC study). Current problems in cancer. 2019;43(5).

- Abigail Cowan RPMaAM. Treatment of Vitamin D Deficiency in Adults. Wirral University Texas; 2020.

- PD C, Division of Preventive Medicine BaWsH, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts., WY C, Department of Medical Oncology DFCI, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts., ON A, A H, et al. Effect of Vitamin D3 Supplements on Development of Advanced Cancer: A Secondary Analysis of the VITAL Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(11).

- MC S, TW F. Does serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D decrease during acute-phase response? A systematic review. Nutrition research (New York, NY). 2015;35(2).

- DANIEL D. BIKLE EG, BERNARD HALLORAN, MARY ANN KOWALSKI, ELIZABETH RYZEN, JOHN G. HADDAD. Assessment of the Free Fraction of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D in Serum and Its Regulation by Albumin and the Vitamin D-Binding Protein. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 2021;63(4):954-9.

- Josefson D. St John's wort interferes with chemotherapy, study shows. BMJ. 2002;325:460.